4 reasons why social change campaigns are no longer effective – and what to do about it

“Don’t f**k with the formula”

In 1966, while Brian Wilson was radically innovating, and creating new works of musical genius, other members of the Beach Boys remained sceptical. Fellow band member Mike Love’s famously bad advice to him at the time (at least apocryphally) was “Don’t fuck with the formula”. Don’t move away from what works, i.e. in their case (formulaic) songs about girls, surfing and cars.

But then again if the formula’s no longer fit for purpose, there comes a time when it’s more risky to stick with it.

It’s important that NGOs don’t end up as the Mike Love of the world of social change.

But when it comes to campaigning, it feels like much of the sector is stuck in the wrong space. There are a set of positions and assumptions that need to be examined and radically reconsidered.

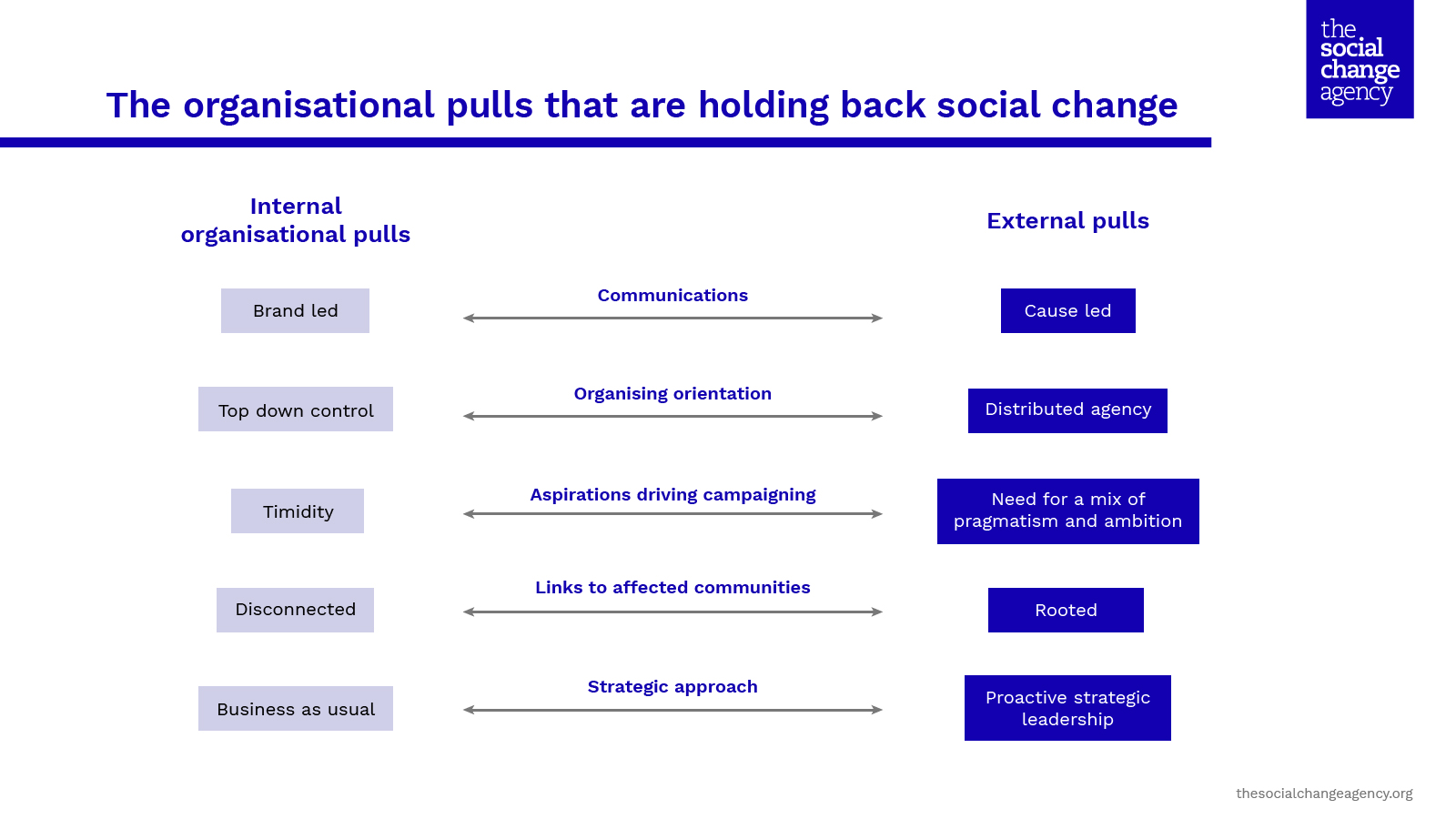

Notably, we see tensions playing out around these core issues:

1. Disconnectedness

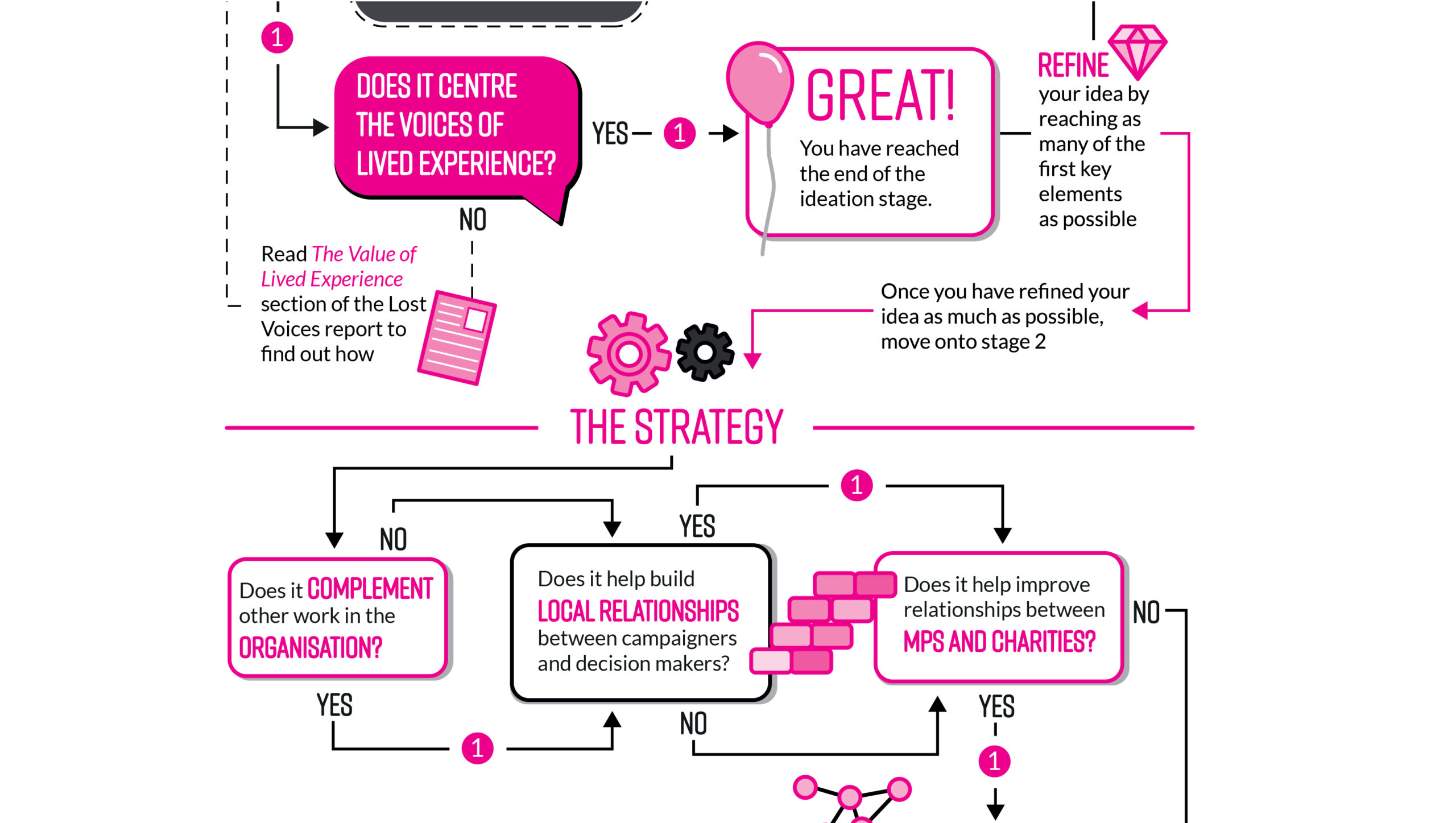

We talk about this in the previous post. There is a pull towards representing and fulfilling the interests and priorities of supporters, which can be at the expense of the quality of links with, and accountability to, the communities that organisations exist to support. See our Lost Voices project for more about the disconnect with those with direct lived experience of the issues.

But even the connections to supporters aren’t always that great. Online campaigning offers a low cost/high volume model of operating in which generating meaningful action or developing meaningful dialogue can easily end up as low priorities .

2. Control

NGOs identify a need for branding and communications coherence and this encourages a desire to exert continuing control over campaigning messages and messengers.

But this approach can constrain the energy of their campaigns and close off routes they could otherwise flow in. And it fails to exploit or build the power of community activism, especially where power could be built by working more closely with unconstituted groups.

Drawing on findings from 47 campaigns, the Networked Change report identifies that, “Groups which allow their supporters to customize and adapt campaign messages and visuals to better suit their local contexts are showing that flexibility pays off in higher engagement rates. They succeed because they are building networks across geographic boundaries that better respect the distinct differences in culture and approach at the local level”.

These campaigns achieved success precisely because of their ability to open up to the new cultural forces that favour openness and grassroots power, but also because they frame and strategically direct this power towards achieving meaningful outcomes.

Not holding onto control is a particularly important principle in joint working. The excellent new handbook from Crisis Action on building and working in coalitions, for example, stresses the importance of subsuming brand and being prepared to operate behind the scenes (“Serve the cause not the coalition”).

At our Justice.Period event last week, we witnessed two campaigns publicly agree to merge petitions to help get free sanitary products to school children who need it. It was a widely, and rightly applauded, but this should be the norm, not the exception.

3. Hierarchy

Centralised control is typically maintained through hierarchical structures. But this can lead to campaigns that are bureaucratic, slow moving, and insufficiently reactive and adaptive.

And there’s growing evidence that more fluid ways of working are likely to be most effective in campaigning. In her developing work on strategic leadership, for example, US academic Hahrie Han stresses the importance of organisations being able to sense how the world around them is changing, and that this relies on responsiveness to constituencies, and the ability to draw resources from those constituencies, through decentralised structures and distributed decision making.

Back in the 80s, Tom Peters was setting out that in complex contexts the best principle is to apply what he called a simultaneous loose-tight model – with boundaries around common strategy and values, but then with maximum operational freedom to implement being delegated to the frontline

So it’s about time the whole sector caught up with this.

4. Timidity

We should celebrate all campaign victories – but looking across the sector if feels like we are mainly fighting rearguard actions against things getting worse. That’s valuable work but it’s important too to be able to look up from this and think more long-term about what can be done to help create more conducive policy contexts. Without this, the space for change will continue to shrink.

One driver of this is that organisational pressures on campaigners to show results are encouraging campaigns that are more about walking through open doors than about seeking systemic change. In conjunction, this all looks something like this.

NGOs need to do more to counter internal pulls that are increasingly out of sync with the realities of social change.

That means ceding control, distributing power and leadership through more fluid and facilitative structures and ways of working, reaching out more,, and thinking more expansively about the dimensions of change.

We know that this is possible because we ran Losing Control, a two day movement-building hack exploring these issues with nine social movements with a range of constituted and unconstituted groups across migrant and refugee and youth and social justice sectors. The NGOs, bar one or two organisations such as Friends of the Earth, were notably absent.

All these areas need thought, to avoid getting boxed into a failing formula. And we’ll talk more about all these things in forthcoming posts

We know it can be hard to make big changes on an organisational level – talk to us to see how we can help